the parliamentary governments of germany in the mid- to late 1920s were dominated by what group?

| |||||

| Decades: |

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| See also: | Other events of 1920 History of Germany • Timeline • Years | ||||

Events in the yr 1920 in Germany.

Incumbents [edit]

National level [edit]

President

- Friedrich Ebert (Social Democrats)

Chancellor

- Gustav Bauer (Social Democrats) to 27 March, and then Hermann Müller (1st term) (Social Democrats) to 25 June, and so Constantin Fehrenbach (Middle)

Overview [edit]

Consider first the territorial changes which had been brought almost by the Treaty of Versailles (and too certain internal territorial rearrangements which had taken identify equally the effect of the revolution). By the Treaty of Versailles provinces had been severed from Germany in almost all directions.

The two near important cessions of territory were the loss of Alsace-Lorraine to France and of a large stretch of territory in West Prussia, Posen, and Upper Silesia to Poland. Of these, the territory ceded to Poland amounted to nearly 20,000 square miles (l,000 km2), and, coupled with the establishment of Danzig as an contained state, which was also imposed upon Germany, this loss had the outcome of cutting off East Prussia from the main territory of Germany.

Danzig and Memel were to be ceded to the Allies, their fate to be subsequently decided. A portion of Silesia was to exist ceded to Czechoslovakia. Also, autonomously from the actual cessions of territory, the treaty arranged that plebiscites should be held in sure areas to decide the destinies of the districts concerned. Sure districts of East Prussia and West Prussia were to poll to make up one's mind whether they should vest to Deutschland or to Poland. A third portion of Silesia, which was in dispute between Germany and Poland, was to exercise the right of self-conclusion. The modest districts of Eupen and Malmedy were to decide whether they would belong to Belgium or to Germany. The middle and southern districts of the province of Schleswig, which had been annexed to Prussia in 1866, were to decide their ain destinies. Finally, the coal-producing valley of the Saarland, which had been provisionally separated from Germany, was to exist the subject area of a referendum after the lapse of fifteen years.

The Allied and Associated governments had assumed the job of revising territorial changes and arrangements dating back to the latter half of the 18th century. The conference cancelled completely the expansion of Deutschland over the past 150 years; but did not cancel the schism in Germany—the exclusion of Republic of austria—which had been incidental to that expansion.

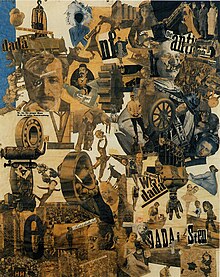

Raoul Hausmann, George Grosz, Hannah Höch and other artists helped plant the Berlin wing of the Dada movement, an avant garde artistic motion that defied the established forms of classical art. Photomontage, a technique Hausmann claims to have originated with Höch in 1918, becomes associated with Berlin Dada style.[1]

Events [edit]

Internal territorial changes in Federal republic of germany [edit]

The following describes the internal territorial rearrangements which were made after the institution of the German commonwealth. During the menstruum of the Hohenzollern empire at that place had been twenty-6 states within the German federation. During the war the number had been reduced by i past the fusion of the principalities of Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt and Schwarzburg-Sondershausen. After the revolution there was a rapid reduction in the number of smaller states. Alsace-Lorraine was, of course, returned to France, and the two principalities of Reuss—the and then-called Elderberry and Younger lines—united into a single land. The Duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha carve up into two halves; Coburg voluntarily united itself with Bavaria, and Gotha afterward in the year 1919 entered into negotiations with a number of the other small-scale states of cardinal Deutschland to bring almost a full general matrimony of the little republics concerned. Half dozen states took role in these negotiations, which were brought to a successful conclusion at the end of Dec 1919. The states which thus agreed to unite were: (i) Schwarzburg, (2) Reuss, (three) Gotha, (4) Saxe-Weimar, (5) Saxe-Meiningen, and (6) Saxe-Altenburg. The total population of the U.s. was just over 1,500,000, and their joint area was just over 4,500 square miles (11,700 km2). The states took the name of Thuringia (Einheitsstaat Thüringen). The town of Weimar was fabricated the uppercase of the new state.

It volition be seen that owing to these various fusions and changes the twenty-half-dozen states of the German federation were reduced to eighteen.

Political situation at the commencement of the year [edit]

In considering the general political state of affairs in the land at the kickoff of 1920, it is notable that from the fourth dimension of the revolution until the end of 1919, the Liberal and Radical parties in combination with the so-called Majority Social Democratic Political party had held ability continuously, and had been strikingly confirmed in their position past the general election held in January 1919. The chief indicate of interest in the full general ballot had been the shut correspondence of the results with those that used to exist obtained in the elections for the erstwhile Reichstag in the fourth dimension of the Empire. On February 11, 1919, the new parliament elected Friedrich Ebert equally president of the German democracy. Philipp Scheidemann acted as minister-president during the first one-half of 1919, simply at the time of the signing of the treaty of peace in June he was succeeded by Gustav Bauer, one of the best-known leaders of the Majority Social Democratic Party, who had not been a member of Scheidemann'southward government. The government persevered but the ministry building and the parties which supported them were placed in an unstable and very difficult position. On i side, the government had to confront the farthermost hostility of the conservative party, who had been opposed from the offset to the new republican institutions. On the other side, they faced the extreme revolutionaries, who, for entirely dissimilar reasons, had been opposed to the submission to the Entente, and desired an alliance with the Bolshevik forces of the Soviet Matrimony. During 1919 the government had been faced greater difficulties from the parties of the left than the parties of the right, and the extreme Socialists had made several unsuccessful attempts at armed insurrection. The reactionary groups were likewise capable of making serious trouble for the authorities.[ citation needed ]

Anti-government agitation [edit]

During January and February at that place were no events of commencement-grade importance, just in March there were kaleidoscopic changes in Berlin, which illustrated dramatically the difficulty of the position of the moderate German language government, placed every bit it was, between the extremists of the right and of the left. During the early weeks of the twelvemonth certain people in the conservative party were agitating actively against the regime, and were endeavouring to find some pretext—preferably a democratic pretext—for taking action against them. Ane of the most prominent persons in this movement was Dr. Wolfgang Kapp, who had once held office equally president of East Prussia, and had been a founder of the Fatherland Political party and an acquaintance of the Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz. During Jan and February Kapp entered into correspondence with the prime minister, Bauer, and brought complaints confronting the government. The main of these complaints were that Ebert had remained in ability too long, since according to the constitution the president ought to exist elected past the whole nation, and not merely (as Ebert had been) by the National Assembly; that the ministry building itself had likewise retained power too long, since information technology and the parliament which supported it were elected and established only for the purpose of concluding peace; that the government's assistants had been inefficient and had failed to restore the economical position in the country, which had remained deplorable since the conclusion of the armistice. In that location was merely fiddling substance in any of these charges, except, perhaps, the outset; and there is every reason to suspect that they were only put forwards as a cover for different, and perhaps sinister, designs. Ebert and Bauer naturally paid no attention to Dr. Kapp's demands; and in the middle of March the reactionaries seem to have idea that the time had arrived for them to come out into the open and declare opposition.

On March 12 Bauer appears to have obtained information regarding the plot, and maybe it was this which induced the conspirators to act before than they had intended and certainly prematurely. Kapp had obtained an important cohort in the person of General Businesswoman Walther von Lüttwitz, who was the commander of the 1st Division of the Reichswehr. Another commander of the Reichswehr, General Georg Maerker, also appears to have been very doubtful in his loyalty to the government. During the past twelve months both these soldiers had served well under the able, but ruthless, cruel, and traitorous war minister, Gustav Noske, in the piece of work of suppressing the insurrections of the Spartacists, a group of anti-war German radicals. Repression of the German pacifists and internationalists, it would turn out, was an activity in which reactionaries and moderates could easily cooperate without friction.

Insurrection in Berlin [edit]

Finding that his plot was discovered, Dr. Kapp attempted a sudden coup d'état in Berlin, which met with fleeting success. Supported by the Marine Brigade Erhardt (the first paramilitary group to use the swastika as its emblem), by the irregular "Baltic" troops (the German troops who had occasioned trouble in Courland in the previous year by fighting independently of any authorities), who were now stationed at Döberitz, past the former baby-sit cavalry partitioning, and by the Reichswehr troops whom General von Lüttwitz had led, Kapp advanced upon Berlin in the early hours of March 13. Realizing that the generals in command of the Reichswehr had betrayed their trust, Ebert and Bauer fled from Berlin to Dresden, and were fortunate in being able to escape before the Baltic troops arrived. Immediately after he reached Berlin, at x am, Dr. Kapp issued a proclamation declaring that the Ebert-Bauer administration had ceased to exist and that he was himself acting as imperial chancellor, and that General von Lüttwitz had been appointed minister of defense. The announcement also stated that Dr. Kapp just regarded his administration every bit provisional, and that he would "restore constitutional weather" by belongings new elections. The new government disclaimed whatsoever intention of restoring the monarchy, but all Kapp's chief supporters were monarchists, and he had the onetime imperial colours—black, white, and ruddy—hoisted in the majuscule. It was also peradventure significant that immediately later on the coup d'état much coming and going was reported from ex-Kaiser Wilhelm II's Dutch habitation at Amerongen.

Ebert and his associates were not ho-hum to decide upon the measures to be taken against the reactionaries. They issued an appeal to the working classes to engage in a desperate full general strike. The entreatment, which was signed by Ebert, Bauer, and Noske, read as follows:

- "The military revolt has come. Ehrhardt'southward naval brigade is advancing on Berlin to overthrow the government. These servants of the land, who fear the dissolution of the regular army, desire to put reactionaries in the seat of the government. Nosotros refuse to bend before military machine compulsion. We did non make the revolution in order to accept once again to recognize militarism. We volition not cooperate with the criminals of the Baltic states. Nosotros should be aback of ourselves, did nosotros human action otherwise.

- A thousand times, No! Stop work! Stifle the opportunity of this military machine dictatorship! Fight with all the ways at your command to retain the commonwealth. Put all differences of opinion aside.

- Simply i means exists against the render of Wilhelm Two. That is the abeyance of all means of communication. No mitt may be moved. No proletarian may assist the dictator. Strike along the whole line."

The response to this appeal past the working classes was enthusiastic and almost universal. Except in East Prussia and to some extent in Pomerania and Silesia, the Kapp "government" obtained scarcely any support in the country; and the Saxon, Bavarian, Württemberg, and Baden governments all rallied to the support of President Ebert—though however the loyalty of the Saxons, the president and the prime minister thought information technology advisable to remove from Dresden to Stuttgart. Kapp and von Lüttwitz met with the biting hostility of the working classes in Berlin, who succeeded in bringing to a standstill the whole life of the majuscule.

It was, indeed, apparent afterward twoscore-eight hours that the extraordinary success of the general strike would make the new Kapp authorities incommunicable. During the showtime two days there were rumours that in order to avoid ceremonious war Ebert and Bauer were willing to compromise with the conspirators; but it soon became obvious that any such form would be unnecessary.

The characteristic which hampered Kapp fatally was the complete success of the strike in Berlin itself; and since his writ did not fifty-fifty run in the capital letter, the usurping chancellor felt compelled to resign on March 17. He endeavoured to embrace up his failure, by alleging that his mission had been fulfilled, in that the government had now proclaimed that they would agree a general election inside a few weeks, just his protestations notwithstanding, it was obvious to all the onlookers that his real designs had been to displace the old authorities altogether, and very probably to upset the entire republican regime. A meeting of the National Assembly was held at Stuttgart on March 18, and the prime government minister made a long speech dealing with Kapp's escapade, but before so, the crisis had already passed—and had in fact given identify to a crisis of a totally different kind. On March 18 some of the members of the authorities returned to Berlin, and on that twenty-four hour period also Kapp'southward troops—who were known as the "Baltic" troops, although the name properly practical but to a department of them—left the upper-case letter. Their divergence was unfortunately marked by a virtually disagreeable incident. Every bit they marched through the streets towards the Brandenburg Gate, the populace which had always been entirely hostile to them, collected in cracking numbers and followed the soldiers, jeering vociferously. The legionaries were in an ill-humour at the failure of their insurrection, and beingness further aggravated by the behaviour of the crowds, when the last detachment reached the Brandenburg Gate they wheeled virtually, and fired several volleys into the mass of civilians who had followed them. A panic ensued, and a considerable number of persons were killed and wounded. Kapp himself fled to Sweden.

Run into as well Kapp Putsch.

Return of regime [edit]

When the authorities returned to the capital, they found that the strike which they had utilized to overcome Kapp had at present got across command; and indeed in the east cease of Berlin, Soviets were being alleged, and Daunig had declared himself president of a new German Communist republic. The government chosen off the strike, but a large number of the strikers refused to return to work. On March 19 Spartacist risings occurred in many different places, particularly in western Prussia, Bavaria, Württemberg, and Leipzig. In Leipzig the rising was extremely serious, and in suppressing this local insurrection the regime had to apply aeroplanes over the streets of the city in social club to intimidate the Communists. The Communist leaders decided to direct the strike, the power of which had been proved against Kapp, confronting the government itself. In Berlin, with the active help of the prime minister of Prussia, Paul Hirsch, the federal government were presently able to gain control of affairs; and in Saxony, Bavaria, and Württemberg the troops were too able to overcome speedily the insurrection. But in the west, in Westphalia and the Rhineland, the situation became extremely serious. The position was in this office of Federal republic of germany complicated by the being of the neutral zone lying between the territory occupied by the Entente, and the main office of Germany, where the government were of course gratuitous to movement their forces as they pleased. Apart from a minor force for police purposes, the German government were not allowed to transport troops into the neutral zone. The armed services constabulary in the zone were quite incapable of dealing with the Spartacist coup; and the insurgents chop-chop took possession of Essen, later a treacherous attack on the rear of the small authorities force. The revolutionists also seized Wesel. The union of "Red" Germany with Bolshevik Russia was proclaimed. The government took alarm at the development of the Spartacist peril, and on March 23 it was even rumoured that a purely Socialist government—containing several members of the Contained Social Democratic Party—was to exist formed. This rumour proved to exist untrue, but two of the ablest members of the cabinet, Noske and Matthias Erzberger, who were especially obnoxious to the Communists, were asked past Bauer to resign. The resignation of these two ministers was in some sense a concession to the extremists, simply the latter refused to consider compromise. Feeling overwhelmed with the difficulty of the situation, Bauer himself resigned on March 26. Fortunately Ebert had no difficulty in finding a statesman willing to undertake the burden of the chancellorship. The president asked Hermann Müller, who had previously held the role of minister for foreign affairs, to form an administration. Within 40-8 hours it was announced that Müller had succeeded in forming a chiffonier, which included (every bit did the previous administration) members of all the iii moderate parties, the Clericals, the Democrats, and the Majority Social Democrats. The new cabinet was equanimous as follows:

| Chancellor and Government minister for Foreign Diplomacy | Hermann Müller |

| Undersecretary for Strange Diplomacy | von Haniel |

| Minister of the Interior and Vice-Chancellor | Erich Koch-Weser |

| Minister of Posts | Johannes Giesberts |

| Government minister of Finance | Joseph Wirth |

| Minister of Transport | Johannes Bell |

| Minister of Justice | Andreas Blunck |

| Government minister of Labour | Alexander Schlicke |

| Minister of Economics | Robert Schmidt |

| Minister of Defense | Otto Gessler |

| Government minister of Food | Andreas Hermes |

| Government minister without Portfolio | Eduard David |

| President of the Treasury | Gustav Bauer |

Müller's tenure of the Foreign Office was only temporary, and before the eye of April he relinquished that position to Dr. Adolf Köster. At the same time there was a reconstruction of the regime of Prussia, Otto Braun condign premier. The new ministry was constituted on much the same lines every bit that of Germany, and including members of all the three moderate parties.

Ruhr Insurgence [edit]

As shortly as he assumed office Müller had to bargain with the pressing trouble of the coup in the Ruhr valley, and the neutral zone generally. The German authorities applied to the Allies for permission to send troops into the disturbed districts in excess of the numbers allowed past the Treaty of Versailles. It appears that in view of the state of affairs which had arisen the British and Italian governments made various suggestions for a temporary modification of these particular provisions of the Treaty of Versailles (Manufactures 42 to 44). Information technology was proposed, for instance, that German forces might be immune to occupy the Ruhr valley nether whatever guarantees Align Foch might think necessary; or that the High german troops should be accompanied by Centrolineal officers; or that the matter should be left in the easily of the German government with a alert that if the neutral zone were not re-evacuated as soon as practicable, a further commune of Frg would be occupied past the Entente. The French regime, notwithstanding, raised difficulties; and alleged that if the Germans were allowed to send forces into the Ruhr District, they (the French) should be allowed to occupy Frankfurt, Homburg, and other neighbouring German towns, with the sanction of the Allies, during the period that the German language troops were in the neutral zone. Owing to these differences of opinion betwixt the Allied governments no quick decision was reached; in the concurrently, the coup in the Ruhr Valley was condign daily more serious. Moreover, the German government themselves hindered a settlement by indicating that they could non have the French proposition of a parallel occupation of Frankfurt by French troops. It was obvious that matters would presently accomplish a crisis, notwithstanding the conciliatory efforts of the British government It came as no great surprise, when, on April iii, German regular troops, of the Reichswehr, entered the neutral zone in force, although no permission for them to do then had been granted past the Entente. The troops were nether the command of General von Watter, and they experienced no serious difficulty in dealing with the Spartacists, although the latter possessed some artillery. The revolutionary headquarters at Mülheim were taken on April 4.

International intervention [edit]

These incidents led to somewhat sensational developments between the French, British, and High german governments. Immediately after the German troops crossed the line, the French government itself gave orders to its own troops to accelerate, and Frankfurt was occupied on April 6 and Homburg on the following twenty-four hours. The French regime proclaimed the necessity of this move on the ground that Articles 42 to 44 of the Treaty of Versailles had been broken by the Germans. The French advance occasioned farthermost bitterness of feeling in Deutschland, more especially as some of the occupying troops were black; and the attitude of the crowds in Frankfurt became so hostile, that on one occasion the French troops brought a motorcar-gun into activity, and a number of civilians were killed and wounded. The British government also disapproved of the French activity, partly because they regarded the advance as an extreme measure which should simply take been adopted in the last resort, and still more than so because the French motion had been made independently, and without the sanction of the other Allied governments. The British held that the enforcement of the terms of the Treaty of Versailles was an affair for the Allies collectively, and non for any single Centrolineal government.

The Franco-British difference of opinion was, however, of short elapsing (see 1920 in France); and information technology was soon made clear that whilst the British government were tending to think that in that location had been a genuine necessity to ship the German troops into the Ruhr valley, they were equally as adamant every bit the French to see that the terms of the treaty were observed. And the extreme rapidity with which the German troops overcame the revolutionaries tended to bring the whole crunch to an end.

On April 12 Müller made a statement on the situation in the National Assembly at Berlin. He complained of French militarism, and in particular that Senegalese negroes should have been quartered in Frankfurt University. He laid the arraign for the developments largely upon Kapp and his assembly; and said that it was owing to the undermining of the loyalty of the Reichswehr by the reactionaries, that the working classes had now lost confidence in the republican army. The latest casualty listing which had been received from the disturbed surface area proved the severity of the actions which had taken place; 160 officers and men had been killed and nigh 400 had been wounded. The advance of the German troops into the Ruhr had been necessary in order to protect the lives and property of peaceable citizens living in that district. It was truthful, said the speaker, that according to Articles 42 and 43 of the treaty of peace, the German government were not allowed to assemble armed forces in the neutral zone, because to do so would institute a hostile act confronting the signatory powers; but, he asked, was this prescription laid down in lodge to forestall the reestablishment of public society? By an understanding of August 1919, the Entente had sanctioned the maintenance in the neutral zone of a military police force, and therefore the Entente, including France, had recognized that measures necessary for the preservation of gild in the neutral zone did non constitute a violation of the treaty.

San Remo meeting [edit]

A coming together of the Supreme Council, consisting of the British, French, and Italian prime number ministers, was opened at San Remo on April 19; and the Council had to deal, among other questions, with the German invasion of the Ruhr Valley, and with the trouble of disarmament generally. David Lloyd George, with the support of Francesco Saverio Nitti, proposed that the German regime should be invited to attend the conference; but this was strongly opposed past Alexandre Millerand, and the proposal therefore lapsed. The result of the discussions at San Remo on the German question was that a note dealing with the question of disarmament was sent to the German government at the end of April. The note declared that and so long every bit the German language regime was not taking serious steps to carry out the disarmament clauses of the Treaty of Versailles, it was impossible for the Allied governments even to consider the German request that the permanent strength of 100,000 men, immune by the treaty, should be increased. Germany was not fulfilling her engagements either in the destruction of the materials of war, or in the reduction of the number of troops, or in the provision of coal, or with regard to reparation. The Allied governments intended to insist upon the conveying out of the terms of the treaty, though in cases where the German government were faced with unavoidable difficulties, the Centrolineal governments would not necessarily insist upon a literal interpretation of the terms. It was not their intention to annex whatever portion of High german territory.

So far equally the occupation of the Ruhr valley was concerned the higher up note came well-nigh subsequently the event as the rapidity with which the Reichswehr overcame the insurgents fabricated it possible for the High german regime to withdraw the troops within a few weeks. At the end of April the foreign minister, Dr. Köster, declared that the French ought now to evacuate Frankfurt, Darmstadt, and Homburg, because the German troops had been reduced to 17,500 which was permitted by the agreement of August 1919. On the Allied side, however, it was stated that the force must be reduced forthwith to twenty battalions, six squadrons, and two batteries; and that even this force would accept to be replaced entirely by a body of ten,000 police by July 10. The German government made the necessary reductions, and on May 17 the French evacuated Frankfurt and the other occupied towns.

General election [edit]

The reactionary and Spartacist insurrections having been thus quelled, the German regime proceeded, in accord with their declarations, to make the necessary preparations for property the full general election. The elections were stock-still for Sunday, June vi. All the parties undertook active campaigns, but the general public showed less interest in these elections for the new Reichstag than they had shown in the elections for the temporary National Associates in Jan 1919. The total number of electors was almost 32,000,000, approximately 15,000,000 men and 17,000,000 women; but only virtually fourscore% of the voters exercised their rights. In the elections of 1919, the results had been strikingly in accord with the last general election for the Reichstag before the war; and had therefore constituted a remarkable popular confirmation of the attitude of the Reichstag bloc during the war. The nowadays elections yielded different results. The three moderate parties had been in an overwhelming majority both in the last imperial Reichstag and also in the new republican National Associates. They were again returned with a majority over the right and left political wings combined, but the majority was at present very small. The High german political parties were now grouped, from right to left, every bit follows: the National Party (the old Conservatives), the High german People's Party (the quondam National Liberals); the Democrats (the former Radicals); the Clericals (the quondam Heart, which now included Protestant also as Catholic Clericals); the Bulk Social Democrats; the Minority or Independent Social Democrats; and lastly the Communists or Spartacists, whose opinions were comparable with those of the Bolsheviks of Russia.

In January 1919, the Communists, presumably realizing their numerical insignificance, had refused to take part in the polling. On this occasion, however, they decided to enter the contest, and 1 of the remarkable features of the elections was the utter collapse of the Spartacists. The satisfaction which the rout of the Spartacists caused to most moderate Germans was, even so, tempered by the success of the Independent Social Democrats, who had for months been growing increasingly more extreme in their views, and were now, indeed, one of the most extreme Socialist parties in all Europe, outside Russia. The total number of deputies in the new Reichstag was slightly greater than in the National Assembly, existence virtually 470, the exact number being doubtful until the destinies of the referendum areas in West Prussia, E Prussia, and Silesia had been decided. The Spartacists won only two seats. The Independent Social Democrats, even so, increased their membership of the house from twenty-two to 80. The success of the Independent Social Democrats was gained, as might have been expected, chiefly at the expense of the Bulk Social Democrats, who had been by far the largest party in the National Assembly. Indeed, the reduction in numbers of the Majority Social Democrats was almost exactly the same as the increase in numbers of the Minority Social Democrats. The total of the Majority Social Democrats fell from 165 to 110. The Clerical electorate, whose strength lay in the west and south, was as always a remarkably constant feature. The Clericals returned with 80-eight deputies, as against xc in the Associates.

Passing to a consideration of the Liberal and Bourgeois parties, one finds that on the right fly of politics at that place had also been a remarkable change. The Democrats fared worse in the elections than any other party. The two parties of the right were returned in far greater strength than they had possessed in the National Assembly. The number of Democrats fell from 75 to 45, which was the more remarkable when the increased size of the firm is considered. The German language National Political party, representing the sometime Conservatives, and even so avowed monarchists, increased their strength from 43to 65. But the most remarkable gains were those of the High german People's Party. This party—the old National Liberals—represented importantly the not bad industrial interests and had been very influential, though not very numerous, under the Empire. In January 1919, they had been almost annihilated at the polls, and had won only 20-two seats. Now, nevertheless, they returned with over sixty deputies.

It will be seen that the elections apparently revealed two diametrically opposite tendencies: a drift from the moderates to the extreme left, and a drift from the moderates to the farthermost right. These two tendencies had affected adversely the Majority Social Democrats and Democrats respectively. To some extent this possibly reflected popular discontent with the existing government, with a trend for the Democrats to vote for the German People's Party and the Majority Social Democrats to drift to the Independent Social Democrats. The exception in this migrate to the political extremes was to be found, with the supporters of the Clerical Party, whose political fidelity was proverbial. It was not the most extreme parties, the High german Nationals and the Communists, who profited past the ministerial discontent, just the German People's Party and the Independent Social Democrats.

The Bulk Social Democrats were notwithstanding the largest party in the country, equally in the house, and secured nigh five,500,000 votes—well-nigh 1,000,000 more than than the respective totals of the Independent Social Democrats and the Clericals, whose strength was about equal. The Democrats secured a little over ii,000,000 votes; whilst the two parties of the right together secured over vii,000,000 votes, almost equally divided betwixt them.

The 2 parties of the right had increased their full vote by some iii,500,000, and the autonomous vote had sunk past about the aforementioned number. The full poll of the Majority Social Democrats had sunk by some 5,500,000, whilst the poll of the Minority Social Democrats had risen by more 2,500,000. When allowance is made for the subtract in the total poll, at that place was virtually no difference in the Clerical poll, equally compared with January 1919. It will exist seen that as between the non-Socialists and the Socialists as a whole, the position of the not-Socialists had markedly improved, and they had, in fact, slightly increased their aggregate poll, notwithstanding the diminution of the full number of electors who exercised their rights.

New chiffonier [edit]

Owing to the changes in the relative strength of parties, it was several weeks earlier a cabinet could be formed; and after several politicians had attempted in vain to form a new cabinet, Konstantin Fehrenbach, i of the most respected leaders of the Clerical Party, succeeded in doing so. What might take been an extremely unstable parliamentary position was avoided by the good sense shown by the German People's Party, who were led by Gustav Stresemann. The German People's Party decided to abandon their position of opposition and their association with the Conservatives, and agreed to unite with the Clericals and Democrats to form a government. The Bulk Social Democrats would not really join a ministry which included the German People's Party, but they agreed to lend the new regime their general back up in the Reichstag. Thus it came nigh that twenty months afterward the revolution an entirely non-Socialist government came into ability in Germany, though it was true that the new government depended partly upon the support of the Majority Social Democrats, whose moderation, however, fabricated them more than comparable to the Radical-Socialists of French republic and to Radicals in other countries, than to the Socialist parties of well-nigh other countries in Europe. Fehrenbach was born in 1852 and entered the Bavarian parliament equally a Cosmic and a representative of Freiburg when he was about thirty years of historic period. He was elected to the Reichstag in 1903 and he became president of that firm in 1918. And in 1919 he became president of the National Associates.

Fehrenbach was able to form a strong cabinet from the personal bespeak of view. Rudolf Heinze became vice-chancellor and minister for justice, Dr. Walter Simons became foreign minister, Joseph Wirth became minister of finance, Erich Koch-Weser was minister of the interior, and Johannes Giesberts was government minister of posts. Noske was not a member of the new chiffonier.

The new chancellor made his first declaration to the Reichstag on June 28, and declared that so long equally the formerly hostile states refused to alter the Treaty of Versailles, the High german government could have no other policy than to endeavour to the best of their power to behave out the terms of that treaty.

Spa conference [edit]

At the coming together of the Supreme Council at San Remo in April it was decided to invite the German government to a conference at Spa, in Kingdom of belgium, in club to settle the questions relating to disarmament and reparations which arose under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. The Spa Conference was held during the first half of July, and Fehrenbach himself attended the conference at which Lloyd George and Millerand were also present. Earlier going into the briefing with the Germans the Allies agreed amongst themselves equally to the proportions of the total German language reparation which should exist allotted to each of the Allied countries. Thus France was to receive 52%, the British Empire 22%, Italy 10%, Kingdom of belgium 8%, and Serbia 5%, the small remaining proportion to be divided among other claimants. Apart from her 8% Kingdom of belgium was to have the privilege of transferring her entire war debt to Deutschland'due south shoulders, and she was too to have a prior claim upon the first £100,000,000 paid by Deutschland. These proportions were settled, simply the total corporeality to be paid by Germany was not decided.

The conference was to have been opened on July 5, and a preliminary sitting was in fact held on that mean solar day, only attributable to the non-arrival of Otto Gessler, the German minister of defense, it was not possible to proceed with the serious consideration of the get-go subject on the calendar, which was the question of German language disarmament. The conference was held under the presidency of the Belgian prime minister, Léon Delacroix, and the Belgian foreign minister, Paul Hymans, also attended. The British representatives, in addition to Lloyd George himself, were Lord Curzon and Sir Laming Worthington-Evans. The master Italian representative was Count Sforza, the distinguished and successful foreign minister. The German chancellor was accompanied past Simons and Wirth.

On the following twenty-four hour period Gessler arrived, and he proceeded at one time to make a formal request that the 100,000 men, which was the limit of the German army allowed by the treaty, should continue to be exceeded, on the basis that it was incommunicable for the government to keep gild with such a small force. Lloyd George and so explained the reasons for the Allies' anxiety. He said that the treaty allowed Germany 100,000 men, 100,000 rifles, and 2,000 auto guns. Germany, however, notwithstanding possessed a regular army of 200,000 men, and also possessed 50,000 automobile guns, and 12,000 guns. Moreover, she had merely surrendered 1,500,000 rifles, although it was obvious that there must exist millions of rifles in the country. During the discussions on the following days information technology transpired from statements made by the main of the General Staff himself, General von Seeckt, that in addition to the Reichswehr there were various other organized forces in Frg such equally the Einwohnerwehr and the Sicherheitspolizei. The Einwohnerwehr alone announced to have numbered over 500,000 men. General von Seeckt proposed that the army should be reduced gradually to 100,000 men past October 1921. A word upon this matter took place between the Allies, and it was decided that Deutschland should be given until January 1, 1921, to reduce the force of the Reichswehr to the treaty figure of 100,000 men. The exact atmospheric condition laid down were that Germany should reduce the Reichswehr to 150,000 men by Oct i, withdraw the arms of the Einwohnerwehr and the Sicherheitspolizei, and consequence a proclamation demanding the surrender of all arms in the hands of the civilian population, with effective penalties in the event of default. On July 9 the German delegates signed the understanding embodying these stipulations in regard to disarmament.

The afterward sittings of the conference were concerned with the question of the trial of the German "war criminals", the commitment of coal every bit a form of reparation, and various other financial matters. It was the question of coal which required the closest attention, largely owing to the extreme demand of France for supplies of coal, and the agreement relating to this affair was signed on July 16. It was decided that for six months later on August ane the German authorities should deliver up 2,000,000 tons of coal per month.

The question of the war criminals referred to in a higher place had been under discussion since the beginning of the yr. The Treaty of Versailles had required that sure persons with an specially evil record in the state of war should be handed over to the Allies. Lists of the main persons coming under the heading of "war criminals" were published past the Allied governments at the end of January. The lists included a number of very well known persons, such as the Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria, Field Marshal Baronial von Mackensen, Full general von Kluck, Admiral von Tirpitz, and Admiral von Capelle. However, the ex-Emperor Wilhelm had fled to the netherlands, and since the Dutch regime definitely declined to manus him over to the Allies, it was generally held, specially in United kingdom, that it was difficult to press forrard very vigorously with the punishment of those who, even so important their positions, had but been the emperor's servants. It was therefore subsequently decided that the German government itself should be instructed to continue with the penalisation of the war criminals concerned. But it transpired at Spa that the German government had been extremely dilatory in taking the necessary proceedings.

Rest of 1920 [edit]

The last five months of the year were much less eventful in Federal republic of germany. The country was still suffering from a shortage of nutrient, though not in the acute degree which was so painfully characteristic of Austria and also of some of the other countries farther e. The German government appears to have made serious efforts to comply with their treaty obligations regarding disarmament and reparation. Thus, in the three weeks following the Spa Conference over 4,000 heavy guns and field guns were destroyed; and measures were taken to obtain the very large number of arms which existed all over the country in the hands of the civilian population. Not bad numbers of livestock were also handed over to the Allies. Thus France received from Deutschland (upwardly to Nov 30) over thirty,000 horses, over 65,000 cattle, and over 100,000 sheep. Belgium received, up to the same engagement, 6,000 horses, 67,000 cattle, and 35,000 sheep.

The financial position of the land remained extremely serious. The total national debt (funded debt and floating debt) amounted to 200,000,000,000 marks, that is, £10,000,000,000 sterling at the quondam prewar charge per unit of substitution. The predictable revenue for the year 1920–21 was 27,950,000,000 marks, and the anticipated ordinary expenditure was 23,800,000,000 marks. There was, withal, besides an predictable boggling expenditure of no less than 11,600,000,000 marks. A heavy deficit on the railways was besides expected. The substitution value of the marking had fallen disastrously since the armistice, and though it rose towards the end of the year, the mark was still reckoned at over 200 to the pound sterling in December.

Various statistics of population were published during the twelvemonth. Amidst other significant features, it was stated that the number of children under five years of historic period, in the whole of the territories of the sometime Hohenzollern empire, had sunk from eight,000,000 in 1911 to 5,000,000 in 1919.

After resigning from the cabinet, Noske became president of the province of Hannover.

Births [edit]

- iii January - Siegfried Buback, Attorney Full general of Federal republic of germany (died 1977)

- ix Jan - Curth Flatow, German dramatist and screenwriter (died 2011)

- 23 Jan - Gottfried Böhm, German architect and sculptor (died 2021)[2]

- 26 January - Heinz Kessler, German politician, military officer and convicted felon (died 2017)

- 8 February - Karin Himboldt, German actress (died 2005)

- twenty Feb – Karl Albrecht, German entrepreneur (died 2014)

- 22 February – Maria Hellwig, German yodeler, popular performer of volkstümliche Musik (Alpine folk music), and television set presenter (died 2010)

- 2 March - Heinz-Ludwig Schmidt, footballer and manager (died 2008)

- 22 March – Helmut Winschermann, High german oboist (died 2021)

- fifteen April – Richard von Weizsäcker, German politician, former President of Frg (died 2015)

- two June – Marcel Reich-Ranicki, German literary critic (died 2013)

- 18 June – Utta Danella, German writer (died 2015)

- five July - Rosemarie Springer, German equestrian (died 2019)

- 22 August - Wolfdietrich Schnurre, High german writer (died 1989)

- seven Oct - Georg Leber, German politician (died 2012)

- eight October

- Maxi Herber, High german figure skater (died 2006)

- Maria Beig, German author (died 2018)[3]

- 31 October - Fritz Walter, High german football role player (died 2002)

- 17 November - Ellis Kaut, German author of children's literature, best known for her cosmos of Pumuckl (died 2015)

- xix December - Alfred Dregger, High german politician (died 2002)

Deaths [edit]

- 31 March - Lothar von Trotha, German military commander (born 1848)

- 12 May – Casar Flaischlen, German poet (built-in 1864)

- xiv June – Max Weber, German sociologist, philosopher, jurist, and political economist (born 1864)

- 18 July - Albert Zürner, German diver (born 1890)

- 18 July - Prince Joachim of Prussia, German nobleman (born 1890)

- 27 July - Thomas Nörber, High german bishop of Roman Catholic Church (born 1846)

- 6 August - Remus von Woyrsch, German fieldmarshall (born 1847)

- 12 August - Hermann Struve, German-Russian astronomer (born 1854)

- 31 August - Wilhelm Wundt, German dr. (born 1832)

- 8 September - Rudolf Mosse, German newspaper magnate (born 1843)

- ii October - Max Bruch, German composer (built-in 1838)

References [edit]

- ^ Elger, Dietmar (2004). Dadism. Tachen. p. 34. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ Gottfried Böhm, Primary Architect in Concrete, Dies at 101

- ^ Kopitzki, Siegmund (7 September 2018). "Konstanz: Dice Stimme Oberschwabens: Zum Tod der Autorin Maria Beig". Südkurier (in German language). Retrieved 11 June 2019.

ruckermovelledilly1971.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1920_in_Germany

0 Response to "the parliamentary governments of germany in the mid- to late 1920s were dominated by what group?"

Post a Comment